In February, 1982, a manic Steve Jobs bounded into the office of Andy Hertzfeld, the primary software architect of Apple's top-secret next gen computer, the Mac (which celebrates its 30th birthday today). Wild-eyed and obviously excited, the 27-year-old Jobs waved his hands around his head and shouted, "Mr. Macintosh! We've got to have Mr. Macintosh!"

Hertzfeld blinked and started at Jobs, uncomprehending. "Who is Mr. Macintosh?" he asked.

"Mr. Macintosh is a mysterious little man who lives inside each Macintosh computer," Jobs reportedly said. "He pops up every once and a while, when you least expect it, and then winks at you and disappears again. It will be so quick that you won't be sure if you saw him or not. We'll plant references in the manuals to the legend of Mr. Macintosh, and no one will know if he's real or not."

Practically trembling with excitement, Steve Jobs continued to imagine all the weird, funny ways in which users would interact with Mr. Macintosh.

"One out of every thousand or two times that you pull down a menu, instead of the normal commands, you'll get Mr. Macintosh, leaning against the wall of the menu," Steve exclaimed. "He'll wave at you, then quickly disappear. You'll try to get him to come back, but you won't be able to!"

What Jobs imagined was the digital equivalent of the Lilliputian orchestras that live inside the stereo which imaginative parents tell their children make every radio work. But instead of just joking about it, Jobs actually wanted to make it happen. Inspired by the revolutionary graphic user interface created by Xerox PARC, Apple had spent the last three years building a computer that would change the world, and here Jobs was, talking about programming an 8-bit version of the Teeny Little Super Guy right into the core of the operating system.

Hertzfeld thought it was awesome.

"Engineers like myself always daydream about building surreptitious little hacks into our software,"recalls Hertzfeld in an account of the meeting. "But here was the co-founder and chairman of the company suggesting something really wild!"

As work progressed on the Macintosh operating system throughout the next couple of years, Hertzfeld and Jobs worked hard to make their dream of Mr. Macintosh a reality. Jobs flew into the office of Apple's marketing team, and told them to start preparing to hint at the existence of Mr. Macintosh in official materials. He also recruited the Belgian artist Jean-Michel Folon -- a famous, well-respected cartoonist and painter who also did the poster for Woody Allen's Purple Rose Of Cairo --- to design the look for Mr. Macintosh. Making a visual pun on the name of Apple's new computer, Folon drew a whimsical character in a fedora wearing a Mackintosh raincoat.

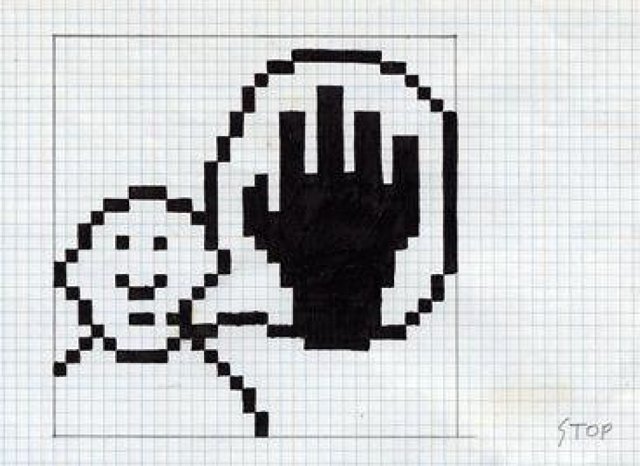

Meanwhile, Hertzfeld programmed some rudimentary hooks into the embryonic code that would allow him to easily insert Mr. Macintosh into the operating system once the animations for the character had been completed. To animate Mr. Macintosh, Hertzfeld approached his old high-school friend Susan Kare. Kare's work on the Macintosh operating system would eventually become legendary; she created a series of icons that is still universally recognizable today. At the time, though, she was unknown: in fact, her work animating Mr. Macintosh was, according to Hertzfeld, the first she ever did for Apple. (Strangely, Kare says she doesn't actually remember working on the character, although she has found a character in her sketchbooks who could possibly be a pixel art mock-up of what he would have looked like in the Macintosh menu bar.)

Everyone wanted Mr. Macintosh to happen. Despite all of this, though, when Apple finally started shipping the original Macintosh to customers on January 24, 1984, Mr. Macintosh was nowhere to be seen, no matter how many thousands of times in a row you clicked the Menu bar. At the end of the day, it was the grim practical reality of early computing that killed Mr. Macintosh in utero.

According to Hertzfeld, what ultimately put the kibosh on Mr. Macintosh was the original Mac's paltry 128 kilobytes of memory. "Eventually, it was clear that we'd never be able to fit the bitmaps for Mr. Macintosh into the ROM,"writes Hertzfeld. Ultimately, the entire Macintosh operating system needed to be refined down to its absolutely must-have features, and a whimsical little man who showed up so irregularly that he would make users doubt their sanity didn't make the cut. Even so, the hooks that Hertzfeld coded into that would allow Mr. Macintosh to appear still exist in the Mac source code. According to Hertzfeld, it would be possible for Mac programmers to create an application or system module that could conjure up Mr. Macintosh (or any other character) as long as they provided their own animations.

Thirty years to the day after the original Macintosh's debut, Mr. Macintosh has been forgotten, even as the computer he was meant to inhabit has gone on to change the world. It's easy to dismiss Mr. Macintosh as a strange whim of a young Steve Jobs, but perhaps that Seussian character dressed in a raincoat deserves more than that. Mr. Macintosh is the initial glimmering of another of Jobs' radical ideas -- a digital person who lives inside your computer who makes using it more fun and approachable. After Mr. Macintosh comes Clippy, Rover, Siri, and Her. He's the primordial man whose descendants will define the user interfaces of tomorrow.