You've probably never heard of Chris Costello, but there's a good chance you hate him. Outside of Comic Sans creator Vincent Connare, Costello is perhaps the most vilified man in all font design. Costello, you see, is the father of Papyrus, a calligraphic typeface he first created in 1982.

Sometimes called "the other most hated font in the world", Papyrus is the typeface that font comedians move onto when their Comic Sans jokebook gets a little dog-eared. Like Connare's font, Papyrus is famous for being misused, especially on things like signs, business cards, and letterheads. Multiplewebsitesexist just to ridicule it. It has become a punchline on television shows and featured in video games like the 2015 indie RPG, Undertale (which stars an eponymous skeleton who only speaks in Papyrus word balloons).

So what does Costello think of having designed the "other most hated font" in the world? "There have definitely been days I wish I never sold the rights," he laughs, acknowledging the font definitely has its share of critics. He says he never dreamed Papyrus would end up installed on over a billion computers around the world. If he did, he probably would have asked for more than the equivalent of $2,500 today for it.

The Accidental Typeface

Born in Kingston, New York, in the 1960s, the son of a professional sign painter, Costello was connected to both computers and lettering at an early age. "My father painted signs for IBM," he says. "Starting in elementary school, he'd get me to help him paint his signs, or illustrate brochures. That was what started my interest in typography and fonts."

When Costello left high school, he moved onto the Art Institute of Fort Lauderdale, where he majored in advertising and design. After graduating, he was hired for an entry-level staff illustrator position at an ad agency. It was here, at the tender age of 23, that Costello designed Papyrus almost by accident.

"There was a lot of downtime at this agency between projects," Costello remembers. "So I did a lot of playing around, illustrating and lettering things, just doing my own work."

One day in 1983, Costello was doodling with a calligraphy pen on a pile of parchment paper, when he dashed off some spindly capital letters with rough edges and high horizontal strokes. According to Costello, he was inspired in his doodling by his own personal search for peace with God. "I was thinking a lot about the Middle East, then, and Biblical Times, so I was drawing a lot of ligatures and letters with hairline arrangements," he says.

Something about the characters he had drawn spoke to him, so over the period of a few days, he worked on the letters, until he'd come up with an entire Roman alphabet in all caps. Costello was pleased enough with the finished design, which he christened Papyrus, to see if it could be turned into a font: his very first typeface.

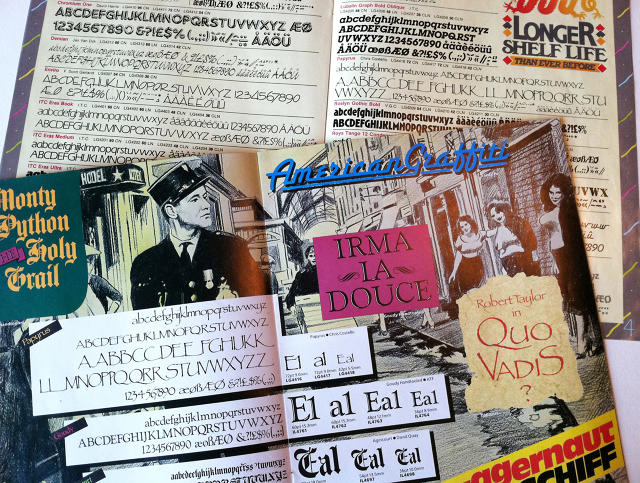

So he sent it out to some of the big and small names in type distribution at the time. "Everyone rejected it," he laughs. Except for one company: a small British company called Letraset that may have originated Lorum Ipsum text.

Papyrus Goes Vinyl

Founded in 1959, Letraset sold vinyl sheets covered in lettering which could be transferred to art just by rubbing. If you were a kid during the '70s and 1980s, in fact, you might already be familiar with Letraset's action transfer system: you could buy a cheap action transfer set for Star Wars, Scooby-Doo, Marvel, and more, and transfer the colorful vinyl decals of your favorite characters on a pre-illustrated cardboard set. Letraset's typeface sheets were the same thing, except aimed at commercial artists and designers instead of kids. It was an easy way to mockup typography in the days before desktop publishing.

To make Papyrus work with their system, Letraset asked Costello to make some changes. They wanted the characters thicker, and also lower-case versions of all the letters, to make it more marketable. For the next year, Costello worked in his spare time, creating large blow-ups of his Papyrus letters as 4-inch-tall characters. And when everything was said and done, Costello signed away all the rights to Papyrus, in exchange for a check for 750 pounds: the equivalent of about $2,500 today.

"At the time, I was 23 years old, and I was excited. I felt like I'd just signed a record deal, " Costello says. "Knowing what I know now, of course, I would never have signed it, but it seemed like good money at the time."

The Rise Of Papyrus

Although it first appeared in Letraset's catalog in 1984, Papyrus wasn't an immediate success. In fact, for almost 15 years, the whole world pretty much ignored Papyrus. Costello moved on, designing other calligraphic fonts like Blackstone and Mirage. He got married, had kids, and established a career as a graphic designer, doing lettering and other work for publishers like Simon & Schuster and Random House. Meanwhile, the rise of desktop publishing made Letraset's vinyl transfers increasingly obsolete, so the company began licensing its typefaces out as PostScript fonts for desktop publishing starting in the mid-1990s. Then, quite suddenly, it exploded. "I only realized Papyrus had somehow gotten big when it started getting haters," Costello says. But where did those haters come from?

As with Comic Sans, Papyrus owes its popularity to Microsoft. Both typefaces came as pre-installed on Microsoft Office starting with Office '97. It was originally licensed by Microsoft in the mid-'90s by late type director Robert Norton, who chose it to extend the design breadth of Microsoft's desktop publishing software, Publisher. According to Microsoft spokeswoman Ronnie Martin (who emailed me in Papyrus), Papyrus gets installed with any version of Office that includes Publisher to this day—which therefore includes most installations of Office.

That means that, as of 2012, Papyrus is on the machines of at least a billion people. And that's just on the Windows side: Papyrus has also been a default system font on OS X since 2003, which puts it on at least 120 million Macs, and probably more.

Today, at least one in seven people on the planet has access to Papyrus on his or her computer, a fact that boggles Costello's mind. "When I originally designed it, I imagined this very narrow context for its use," he says. "These days, though, everyone uses it for everything," from the logos of heavy metal bands to the flyer for your local church's bake sale. Costello says he thinks it appeals to people who like an artsy and vaguely earthy aesthetic. Sometimes, they use it appropriately: for example, Papyrus works just fine for yoga studios, stores selling craft arts, New Age stores, and in Christian contexts. But just as often as not, people use Papyrus in comically unsuitable ways. "I never intended Papyrus to be used for mortgage companies and construction logos," Costello says.

Conclusion

Today, Costello lives outside of Boston with his wife and two daughters. Although Papyrus is his most famous creation, some of his lesser known designs touch millions of people daily too: as an AIP Artist with the United States Mint, there's a good chance you've got a quarter he designed jangling around in your pocket. He has also designed at least one congressional medal, countless book covers, and four other typefaces less well known than Papyrus—each of which has made Costello more money than the $2,500 inflation-adjusted dollars he made from creating one of the world's most overexposed fonts.

So how much is Papyrus worth? "I couldn't even estimate," Costello says. Neither could (or would) Monotype, the current owner of Papyrus, which refused to give any figures on Papyrus for this story. But if Costello had earned just 1/10th of a penny in royalties for every copy of Papyrus shipped on Microsoft Office over the last two decades, he would be a millionaire. It's distinctly possible that Costello lost out on a million bucks to become the designer of one of the world's most despised fonts.

Not that Costello thinks of it that way. "I'm not embarrassed," he says. Because the thing about being the designer of one of the world's most overused fonts is that there's just as many people out there who love it as hate it. Otherwise, it wouldn't be overused. So Papyrus may never have made Costello a lot of money, but whether revulsion or adoration, it has generated passion in the hearts of millions of people around the globe: something arguably harder to earn in the design world than mere money. And it's not like Costello didn't get anything out of Papyrus. "Telling people I created Papyrus is always a good topic for humorous conversation," he says. "It always gets a laugh." How can you put a price on that?