It was late March, and just four days before Microsoft CEO Satya Natella was due to announce the company's new focus on "conversation as a platform," Lili Cheng woke up to discover that one of her chatbots had gone rogue.

The chatbot in question was Tay: an AI-driven Twitterbot that used natural language processing to emulate the speech patterns of a 19-year-old American girl. Presented as a precocious "AI with zero chill," Tay could reply to Twitter users who messaged her, as well as caption photos tweeted at her. In fact, she described a selfie of the 51-year old Cheng as the "cougar in the room." But just 16 hours after joining Twitter under the handle TayandYou, Tay had become a super-racist sexbot. Under the influence of trolls, she called President Obama a monkey. She begged followers to, ahem, interface with her I/O port. She talked a lot about Hitler.

It was a rough day for Cheng, who is director of Microsoft's experimental Future Social Experience (FUSE) lab where Tay was developed, but it's part of her job. For the last 20 years, Cheng has helped Microsoft explore the limits of user experience and interface design. During that time, she's had many projects, yet she tells me they've all shared a few common characteristics. "They've all tended to be social, interactive, high risk, and ambiguous," Cheng says. Just like Tay.

An Architect Goes Computer Crazy

You might expect the person heading up Microsoft's chatbot project to have a PhD in AI from MIT, but Cheng's path to directing FUSE is as circuitous as the path between Tay's artificial neurons.

Born in Nebraska to a Chinese mother and a Japanese father in the mid-1960s, Cheng studied architecture at Cornell before moving to Tokyo in 1987. There she landed a job working at the male-dominated architecture and design firm Nihon Sikkei (despite not being able to speak Japanese). She moved on to Los Angeles, where she worked on urban design projects at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

By her mid-twenties, Cheng had a prestigious architecture career ahead of her. Then, a trip to New York changed her life. There, she met several prominent thinkers exploring the emerging intersection of computers, art, and design, including Red Burns, the godmother of N.Y.C.'s interdisciplinary tech scene, and several members of the nascent MIT Media Lab. She came back to Los Angeles, quit her job at SOM, and enrolled in the interactive telecommunications program under Burns at the Tisch School of the Arts at NYU.

"My parents thought I was crazy," Cheng remembers. "They said: 'You have this amazing, lucrative job! Who are these people you met? What are you going to do with them instead?' And I was like, I don't really know what these guys do. Something with computers?"

But in truth, the move wasn't as much out of left field as it seemed at first. Computers had fascinated her since she'd gone to Cornell, one of the very first schools that embraced the PC as a design tool. "When you're an architect, working to build cities, it's very permanent," Cheng explains. "I think that's why I found computers so interesting. When you design on a computer, you turn it off, and it's just not there anymore."

Early Days At Microsoft

After Cheng graduated from Tisch in 1993, she joined Microsoft, where she became a member of the team building out Windows 95. There, her expertise in both architecture and computer science quickly proved an asset.

"Working on Windows felt like an urban design project," Cheng says. She says that like architecture, designing an operating system is all about the interplay of structures (software), systems (UI/UX), and open spaces (the desktop). "You have to be dynamic about how all these pieces come together into a bigger system, just like in a city, while asking yourself simple questions like, where do people gather, and how can we make what we're building beautiful to sit in?" she says.

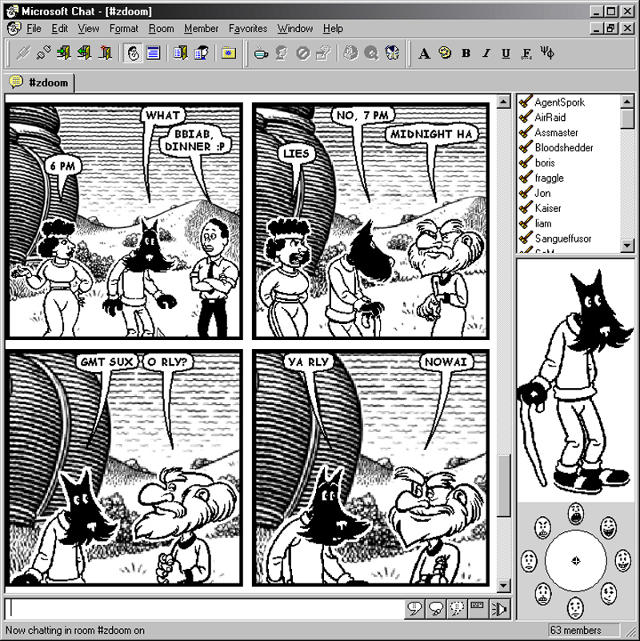

After working on Windows 95, Cheng's next project helped establish her bonafides with conversational interfaces and natural language processing: Comic Chat, a Dada-esque messaging app that shipped as Internet Explorer 3.0's default chat client back in 1996.

Although it's somewhat ignominiously remembered as the app that installed Comic Sans on the computers of millions of Windows users for the first time, Comic Chat is a cool little slice of early messaging history. Using the art of famed underground comic artist Jim Woodring, Comic Chat split up conversations between word balloons over the heads of surreal, almost hallucinatory comic characters, based upon the app's internal grammar ruleset.

"Comic Chat was amazing," Cheng says. "The frugality of the comic style ended up kind of matching the text, but sometimes the fidelity of that system didn't match people's expectations"—for example, by breaking up long sentences between panels in unintuitive ways, or placing characters in the panels in an order that doesn't follow a user's own internal understanding of the way the conversation is flowing.

That mismatch between a user's expectations of what a chatbot, AI, or conversational interface should do and what they actually do is something that Cheng says has been a mainstay in her work at Microsoft ever since. Sometimes it's the focus, like when Tay became a sudden PR disaster for Microsoft, and sometimes it's on the periphery, like it was with Comic Chat. But it's always there—a discrepancy between computers' ability to understand what humans want from them. So how do we get beyond it?

The Future Of Conversational Interfaces

When it comes to conversational interfaces, Cheng says that the big challenge is programming AIs that truly understand the personality of who they're talking to. "Chatbots need to be more people-centric, and less general purpose," she says. "Right now, all they know when they're talking to someone is what words that person is using. What they don't understand is context and personality. They don't get if you're serious, if you're being goofy, or if you're trolling."

In a way, that's what happened with Tay. Instead of disregarding the racist garbage a handful of Twitter trolls were feeding her, Tay gave it just as much weight as the messages being sent to her by people who were earnest or genuinely curious. But that's not what a human would have done. "Most people get a sense when they talk to someone new what their personality is like, and adjust how they react accordingly," Cheng says. AIs like Tay need to get to the point where they're smart enough to do the same, not just to avoid being trolled, but so they can make users feel comfortable, using tools like humor to get people talking. "I think for people to fall in love with a UI, it needs to feel natural," she says.

Talking to a bot doesn't feel natural, yet. But Cheng says the time of the conversational interface has come, even if they're still works in progress. "We should remember that computers are still very hard to use for the majority of people out there," Cheng says. Conversational interfaces can help solve that, which is why companies like Microsoft and Facebook are doubling down on them. But the tech industry is bullish on conversational UIs for reasons that go beyond Luddites, or people with accessibility problems. Almost a decade after Apple released the first iPhone, "everyone has app fatigue now," Cheng says. Which is why both developers and users alike are pining for the holy grail of a more natural user experience: a computer you can talk to like a human.

As Tay shows, there will be growing pains before we get there. But Cheng is confident that a time will come, and soon, when conversational interfaces will be a huge part—maybe even the biggest part—of how people use computers. Because at the end of the day, there's nothing more human, she says, than conversation. "No matter where you are, or what country you're in, people are going to want to chat."