For years now, we've been hearing about how the Internet of Things will connect every object in our homes. And for years, the vast majority of those objects stay dumb.

"What companies are struggling with when it comes to the broad label of the IoT on the consumer side is what the actual problem trying to be solved is," says Rob Chandhouk, president of the sensor startup Helium. "Look at Samsung's new smart fridge, which they're marketing as the hub for your home. Do you think of your refrigerator as a hub?"

Chandhouk doesn't believe that the IoT will be making any big breakthroughs with consumers any time soon. Instead, Helium is betting big IoT's real utility is on the commercial and industrial side of things. It looks like numerous big players agree, based on a recent $20 million Series B funding round including Alphabet's investment arm GV, previously known as Google Ventures. But it's another investor in the latest round that gives us our clearest hint of where IoT is going: Munich Re, an insurance and risk management company.

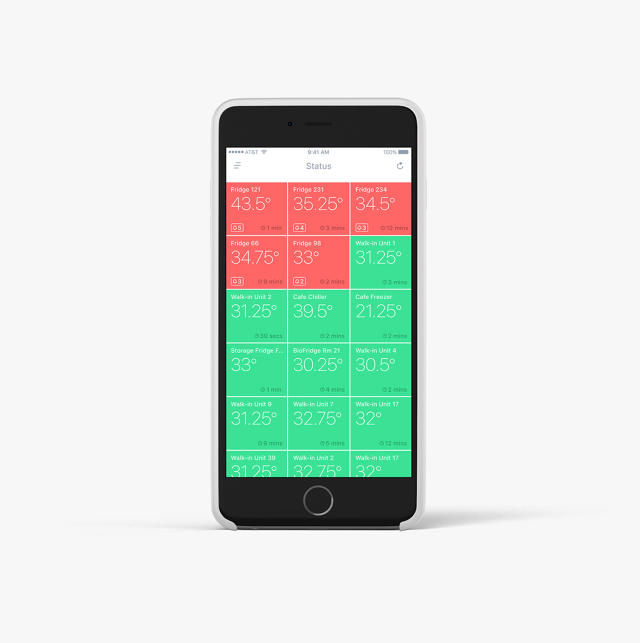

Why would an insurance company invest in the IoT? To understand, first we need to talk a little about what Helium does. The company sells smart sensors, about the size of a deck of cards, which can measure temperature, pressure, light, humidity, barometric pressure, and more. The sensors are wireless, and can run for up to three years without any power. Even better, they run apps, so they can be custom-tailored to send out alerts if, say, they detect that the temperature is too low, or the humidity too high. All of Helium's sensors are designed to be secure, and they're painless to install: You just slap them on the wall and tell them what you want to do through a smartphone or web app.

The value of a box-full of secure, easy-to-install, Internet-capable sensors might have abstract value on the consumer side of things. But on the enterprise side, the value is immediately apparent. A hospital could install a Helium sensor in its drug refrigerators, and get alerts the second the temperature gets too cold. A restaurant could do the same thing if someone accidentally leaves the freezer open overnight. Retail stores could use Helium to figure out that sales in their stores drop by 1% per degree Farenheit when the thermostat is set over 70. "What it boils down to is this: How do you detect information from the physical world, and bring it into your business?" Chandhouk says.

With that in mind, it's easy to see why insurance companies are interested in Helium. "If you're a restaurant insurer, and you have to pay off a quarter-million dollar claim because someone left the refrigerator open overnight, you'd want some way to detect that as soon as it as possible, so that claim can be avoided," Chandhouk says. "In the insurance industry, loss prevention is the name of the game." Alphabet's interest also makes sense. Not only is there potential to make huge money in enterprise IoT, but Helium could one day give Google the physical tools with which to make sense of the world.

Consumers may still not quite understand the appeal of the IoT, but the bean counters sure do. Which is why Helium might be a sign of what's to come. In the future, you might not have to pay to make your home into a smart home. Your insurance company might just subsidize it. You might not be willing to install a $200 sensor that turns off your water when it detects a leak, because those leaks don't happen very often. But an insurance company faced with a $10,000 water claim damage to pay? That's a steal.