Users hate them. They're bad for business. So why do they persist?

Since October of last year, Microsoft has been sending customers of Windows 7 and Windows 8.1 desktop pop-ups, asking them to update to Windows 10 for free. About a month ago, users who had resisted the Windows 10 siren call suddenly found themselves being tricked into updating, when Microsoft made clicking the pop-up's bright red "Close" button actually initiate the update instead.

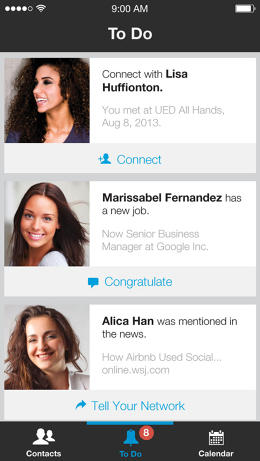

This is a dark pattern: a misleading or otherwise deceptive UI/UX decision that tries to exploit human psychology to get users to do things they don't really want to do. Dark patterns are pretty much as old as the web. The classic pop-up ad, saying you've won a random sweepstakes, is a less sophisticated version of the bait and switch Microsoft pulled. Users hate them. Experts say they're bad for business. So why do they persist? The answer suggests that design is not as prevalent at a strategic level as many companies would have you believe.

Know—And Name—Your Enemy

Since 2010, UX designer Harry Brignull has been cataloging examples of dark patterns online at his website DarkPatterns.org. A few years before Brignull launched the site, he was pickpocketed. "This group of people came up to me, for all appearances out for a night on the town, and one who seemed friendly tried to dance with me," he remembers. When he found his wallet missing, Brignull did a search online and discovered what had happened to him had a name: the drunk dancer technique. "I realized that now that I knew the name for what had happened to me, I would never fall victim to it again," Brignull says. "That's empowering. Naming something deceptive is a way to give you control over it."

Brignull started DarkPatterns to help empower users who had fallen prey to UI/UX scams by naming the deceptive techniques. He specifically gave each family of dark pattern he catalogued a provocative name, so that people could remember what they were. For example, a company that makes it almost impossible to delete your account or unsubscribe is a Roach Motel, after the famous cockroach spray tag line: "They check in, but they don't check out!" A Zuckering, meanwhile, is named after Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and describes a UI that tricks users into sharing more information about themselves than they really want to. And some dark patterns are so ubiquitous that they're industry standards. Try to think of a major publisher or subscription-service provider that doesn't use forced-continuity dark patterns to automatically bill your credit card at the end of a so-called "free" trial.

Why Companies Use Dark Patterns

Over the years, Brignull has caught some very big names using dark patterns, including Microsoft, Facebook, Skype, LinkedIn, TicketMaster, LiveNation, Amazon, Adobe, Wired, the Boston Globe, and many, many more. But why do these companies use them?

Mostly, because they work—in the short term. "In most organizations, designers are just implementers; they're not responsible for strategy," Brignull says. Many designers, and possibly even most, hate using dark patterns in their work, but they are forced to implement them by managers. These managers only care about one or two individual metrics, not the experience of the site or brand as a whole. So a manager who is tasked with increasing the number of people who sign up for a company's newsletter might order a website designer to use a dark pattern to capture email addresses, because it's an easy short-term solution that doesn't really require any effort.

Take LinkedIn. The company was forced to settle a $13 million class-action settlement for surreptitiously sending emails on users' behalf. That would seem to be a victory against dark patterns, except that most companies would be happy to pay only $13 million in legal fees to experience the sort of explosive growth LinkedIn achieved using dark patterns in a few years. Even sites like Netflix use slightly less nefarious dark patterns to convert a seven-day free trial into a subscription, by automatically billing your credit card at the end of it.

But dark patterns are short-sighted, says Hoa Loranger, vice president of the prestigious UX consulting firm Nielsen Norman Group. "Any short-term gains a company gets from a dark pattern is lost in the long term," she says.

The Problem With Dark Patterns

Loranger would know. At NNG, Loranger and her colleagues are often called in by clients when a dark pattern, which previously had led to short-term gains, starts backfiring. "When we work with potential clients, we often hear them say: 'Hey, we did this misleading thing and immediately saw a boost in our numbers. Now it's not working anymore; our numbers are going down. Help us fix it,'" says Loranger. "We then have to explain to them that there are no short-term fixes. They have to design their user experiences in a way that treats their customers with respect."

The reason dark patterns don't work in the long term, explains Loranger, is that a loyal customer is always more valuable than a new customer. "Loyal customers are willing to pay more for your products, engage with your brand on social media, and recommend you to their friends," she says. Dark patterns might result in a boost in new customers, but they're less likely to be loyal customers because they'll soon realize they've been tricked.

Dark patterns aren't just damaging to a brand trying to win new customers. They can also be damaging to brands trying to retain customers. One example Loranger cites is the way that many subscription websites make it easy to sign up, but incredibly obtuse and difficult to unsubscribe—for example, by requiring a person to call, or to send an email. "In these cases, the company has made a conscious choice to use good design principles for the sign-up experience, but bad [design principles] for unsubscribing," Loranger says. "The reason this backfires is because you don't know why a customer is unsubscribing. They could have been laid off, or be going on a long vacation." In other words, by making the unsubscribing process antagonistic, a brand that is just trying to retain subscribers actually has the opposite effect and drives them away.

The Big Picture

Asked if she's ever seen a dark pattern result in a long-term benefit to a client's business, Loranger is blunt: no. So why do companies keep on using them? "I think there's a pressure nowadays on teams to meet or exceed their business goals, to constantly grow at a faster and probably unsustantaible rate," she says. This pressure ends up making even good companies adopt dark patterns to satisfy very short-sighted aims (see Microsoft).

Brignull, though, thinks the atmosphere is getting better. He argues that as companies elevate the role of designers within their organizations to management roles, the tendency to adopt dark patterns will drop. Sophisticated tools are also making dark patterns less alluring to companies, he says. Even just a few years ago, A/B testing to quantify the effects of design decisions was out of the reach of most organizations, says Brignull; today, anyone can sign up for an easy-to-install A/B testing tool. This makes it easier for organizations to quantify the benefits of honest design decisions, such as changing the color of a link, or increasing font sizes, as opposed to defaulting to a dark pattern at the expense of brand perception as a whole.

Ultimately, Brignull and Loranger argue, companies that use dark patterns are at a long-term competitive disadvantage against companies that don't. "If you manipulate your customers, eventually, they won't be your customers anymore," Brignull says. "It's just a matter of time before a competitor comes along who provides a better experience. If your business depends on dark patterns to succeed, you're just leaving yourself open to being disrupted."

All Images (unless otherwise noted): via Darkpatterns.org