For the design-minded, is there anything as satisfying as taking an unordered jumble of things and organizing it neatly? From sorting candy by color to artfully arranging trash, the Internet has long enjoyed ordering the world according to some aesthetically pleasing classification, then showing off the results.

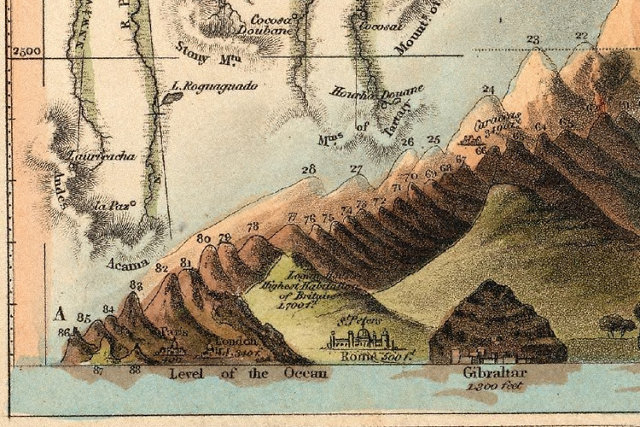

We 21st-century meme followers aren't the first to delight in organizing the inherently unorganized, though. Consider this beautifully illustrated chart: the Comparative Heights of the Principal Mountains And Lengths of The Principal Rivers in The World. First published in 1823 by William Darton, this chart by W.R. Gardner rips the mountains from the skin of the Earth and re-arranges them in ascending height, while simultaneously doing the same for the globe's biggest rivers, ironing their kinks and curls in order to compare for length. This is Victorian data viz at its finest.

Not only does it put the size of mountains and rivers in perspective at a glance, but it also shows how high the mountains are compared to sea level, and even includes interesting facts to put the heights in perspective: pines, for example, are able to survive at the top of some of the Alps, while lichen will not survive above 18,000 feet.

What's also fascinating about Gardner's chart, from a modern perspective, is how much he gets wrong. In 1823, the world was still a largely undiscovered place.

The year this chart was published, the six tallest mountains of the world had yet to be discovered or, at any rate, recognized at such. The tallest mountain that Gardner acknowledges is Dhaulagiri. Gardner gets the size right, more or less--he thinks it's 26,468 feet tall, although it's actually a couple hundred feet taller--but there are several taller mountains, including the obvious contenders of Mount Everest and K2.

This was a time in which summits higher than 20,000 feet might as well have been as distant as the mountains of the moon. Although Jacques Balmat and Dr. Michel Piccard had successfully reached the top of Mont Blanch in 1786, all of the taller mountains on this chart would go unconquered until the 20th century. The highest mountain on Gardner's chart, in fact, wouldn't be fully climbed until 1960.

Gardner's tidy flattening-out of the globe's longest rivers also got some stats woefully wrong. Gardner claims the Nile--the world's fifth longest river, according to the chart--to be only 2,686 miles long. In actuality, at 4,258 miles long, it's the world's longest river, but it would be another 40 years before Sir Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke would identify Lake Victoria as the river's source, allowing the Nile to earn that top slot.

This chart is a captivating testament to our passion for seeing the chaos of the world put into a more logical, mathematical order. That desire may not have changed in 200 years, but our knowledge of that world sure has.

(Hat-tip: Bibliodyssey)