For over 50 years, Florida and other sunny Southern states have experienced a migration pattern: the influx of the snowbird, a not-so-rare breed of Northern-state dwellers seeking to escape winter by flocking south to join their sunbird counterparts. But now a reverse trend is taking shape: Some sunbirds are moving out, spurred by the escalating impacts of climate change.

New research is shedding light on population changes across the South, especially in places already significantly impacted by climate change like Florida and Texas. Heat seems to be playing a role in this northern migration, but that doesn’t tell the whole story—people are also relocating on a smaller scale within cities, out of communities that are flooding with increasing frequency.

Heat is driving people north

The U.S. South has always been hot, which made it a challenging place to live before the 1960s. The high heat and humidity could mean heat illness or even death for those without adequate ways to cool down. But then came air conditioning, a lifesaving invention that transformed the landscape. In fact, despite warming trends due to climate change, heat-related deaths are still down by about 3,600 per year thanks to widespread HVAC systems.

As a result of this new indoor comfort, Americans flocked to the South in droves. Snowbirds, tired of the bitter cold of the North, became notorious for moving to a warmer climate in their golden years—but it wasn’t just retirees. Populations in counties in the South boomed across every age group and education level.

That is, until recently.

Sylvian Leduc and Daniel J. Wilson, both researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, looked into migration trends and found a clear signal: Fewer people are moving South.

Their study, “Snow Belt to Sun Belt Migration, End of an Era?” looked at the change in population in counties that experience both extreme cold and extreme heat. From the 1970s to the 2010s, there was a consistent signal of growth in communities in the South that experienced extreme heat days.

But now the authors find that some U.S. residents are moving away from areas where extreme heat is on the rise, a shift they attribute to climate change.

Just how hot is hot?

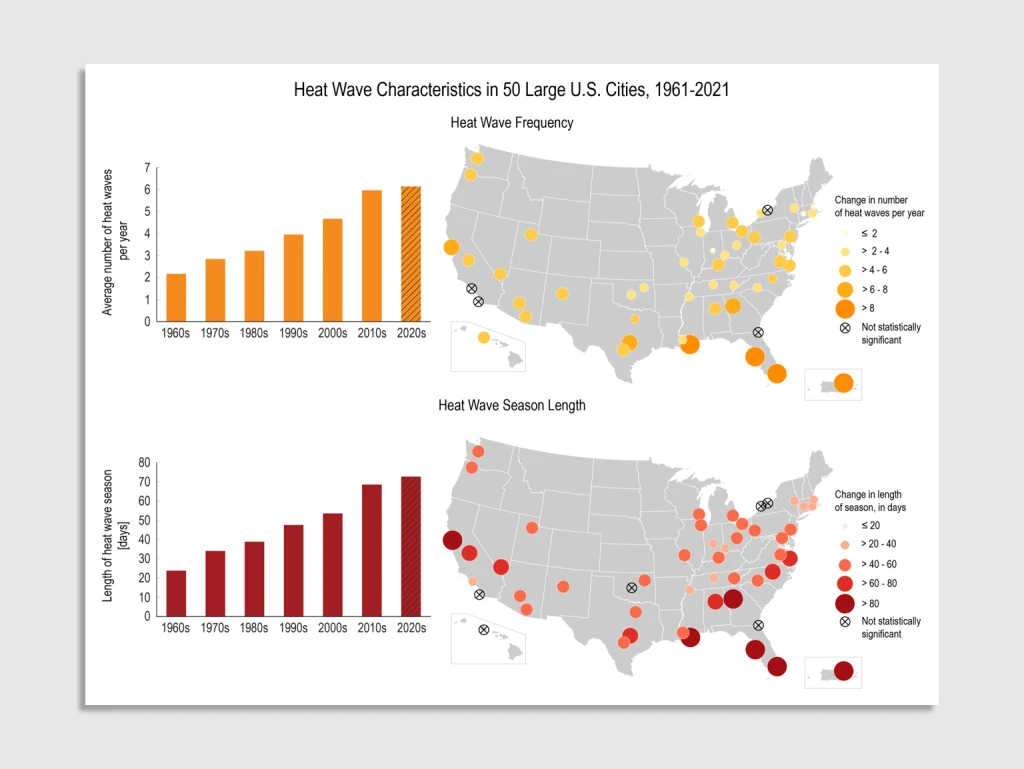

With rising global temperatures, it’s not surprising that our hottest days are also on the rise. Heat waves, defined as two or more days of extreme heat, are increasing almost everywhere, but in the U.S., the trend is pronounced in the South.

The above graphs use data from long-standing weather stations monitored by NOAA.

Places like Miami, Tampa, and New Orleans aren’t just experiencing a little more heat than they did in the 1960s when AC first moved to town. They’re experiencing more than eight additional heat waves each year. Not only that, those heat waves are lasting longer and the season they occur in has increased by more than 80 days.

In the same vein, days considered to be extremely cold are on the decline.

In the above map depicting the change in the number of unusually cold days since 1948, it’s a veritable Where’s Waldo to find the spots that have seen any increase. The communities that have seen a decrease in extreme cold days dominate the map.

Leduc and Wilson said this shift is adding to the reversal of trend and sending, or keeping, more people north.

Their study also looked at demographics and found that the population wasn’t shifting equally—early-career, well-educated professionals and retirees saw the most significant shift away from the South. Both groups are traditionally the most mobile. Snowbirds have long flocked South for their golden years to escape the cold, but the study found those numbers have reversed over the past 10 to 20 years.

Escaping the flood

With climate change causing more heavy downpours and sea level rise, floods are happening more frequently. And that is causing big shifts in how and where Americans choose to buy property.

Forty percent of the population lives near a coast, where sea level rise is contributing to flooding. While on average it has risen five to eight inches, it is rising faster along the East and Gulf Coasts. This means when hurricanes threaten these areas, they are causing even higher, more destructive storm surge.

South Florida, where sea levels have already risen by a foot and could add an additional two feet by 2050, is a glaring example of the trend. Jeremy Porter leads climate implications research at First Street, an organization that links climate change with financial risk. He said that in Miami, tidal flooding received so much media coverage in recent years that homebuyers began purposefully avoiding flood-prone neighborhoods because they’d seen them on the news.

Porter and his team have studied the migration patterns of people living in flood-prone areas with a fine-tooth comb. Their research found 818,000 “climate abandonment area”—locations that had lost population directly due to flooding risk that had increased due to climate change. That added up to 3 million people having moved with an additional 2.5 million expected to leave areas with a high flood risk over the next 30 years.

The study was able to identify moves that others had missed: those that happen locally. Unwilling to stay in a home under increasing threat of flooding as a result of climate change yet unable to leave a city due to jobs or family, people are moving out of flood-prone neighborhoods while staying within their community.

Hurricanes Ian, Helene, and Milton have all caused significant damage to parts of the west coast of Florida in the last two years. Porter said the destruction will likely drive yet more population change in the near future.

“There’s this one rare event that happens and they can’t remember any other ones, people don’t respond to that,” he said. “But if you’re getting hit by an event and then next year you’re hit by another event and then maybe two years out you’re hit by another, people eventually tire of that and they’ll move away.”

Whether climate change impacts are forcing people from their homes due to flooding or they are leaving by choice for a cooler future, the migration patterns in the U.S. are changing—with profound potential consequences for Southern communities if climate change goes unchecked.

—By Kait Parker