One quality that seems to define humanity isn't just its compulsion to create art, but to create art in the most impractical ways. For proof, look no further than Typewriter Art: A Modern Anthology, by graphic designer Barrie Tullett. It's a visual history of more than 100 years during which artists have used their typewriters not to write words, but to create graphic art.

Most Internet-savvy readers are familiar with ASCII art, in which letters, numbers, and other alpha-numeric characters are laid out to resemble pictures. A smiley face emoticon is a very simple kind of ASCII art, but so is this stunning monochrome recreation of the Mona Lisa. Back before multimedia took over the Internet, in the 1980s, ASCII art was a fairly common way for people to send graphics to each other, especially on electronic bulletin boards.

But as Typewriter Art proves, the techniques behind ASCII art are far older than the computer. In fact, the process, called art typing, is almost as old as the typewriter itself.

The first typewriter, the Hansen Writing Ball, was released to the public in 1870. But within just a few years, artists were starting to hack typewriters, and used the machines to produce art, not just letters.

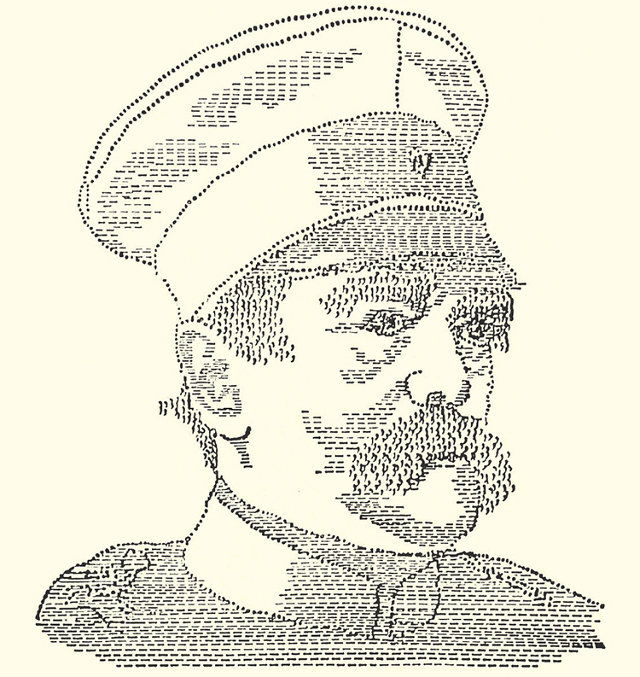

Some of the oldest examples of the practice, according to Typewriter Art, date from the 1890s, courtesy of an English stenographer named Flora F.F. Stacey who pecked out incredibly detailed images of Christopher Columbus, the Santa Maria, and a butterfly, letter by letter. According to Barrie, Stacey is a good example of the type of person who first began to use typewriters to create imagery. Typewriter art was created by people with backgrounds in secretarial studies, so they tended to make art out of the subjects they studied in school.

By the 1920s, however, art typing began to be explored as a technique by professionals, such as Bauhaus artist H.N. Werkman. And in 1950, art typing became the backbone of an entire artistic movement: Concrete poetry, in which the typographical arrangement of characters on a page conveyed the poem's content and meaning as much as the words did. As a movement, concrete poetry petered out by the 1970s--just about the time that the advent of personal computers allowed art typing to make the jump to ASCII.

Historically, every method of using words has been turned into a method of making art. In medieval times, for example, artists in what is now the Middle East used elaborate calligraphy to turn religious texts into pictures. But to Tullett, the typewriter represents a particularly unique medium for creating art.

"The machines have such variety, with different point sizes, font choices, ribbon colors, and so on," Tullett tells Co.Design. "And by using all of these elements in unique ways, artists have turned this rigorous, unforgiving grid into an emotive, fluid, organic thing that can be exploited to produce art."

As for the future of art typing? "I think there will always be people who use typing to make art," Tullett says. "It used to be if you used type to make art, you felt like some eccentric loner, but with the advent of the Internet, there is now a sense that if you're an art typist, you're part of a community." (Tullett laughs.) "Mind you, I think if your preferred medium to make art is a typewriter, you're probably still quite eccentric," she says.

And she should know. An art typist herself, Tullett has been working to complete her magnum opus, a typographical interpretation of the Divine Comedy called A Typographic Dante, for 25 years.

Buy a copy of Typewriter Art: A Modern Anthologyhere.